Kerin O’Dea: the power of traditional diets. By Paula Goodyer

Paula Goodyer

Paula Goodyer

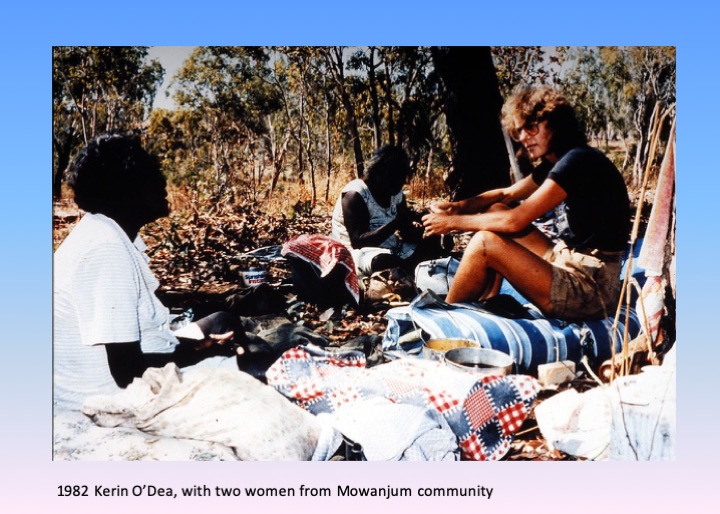

In 1982 a young scientist called Kerin O’Dea went into the wilderness - literally - to study the health effects of a hunter gatherer diet and lifestyle on indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes.

The results of this study in WA’s Kimberley region were dramatic: they found that combining unprocessed wild foods with physical activity could improve health more effectively than a drug.

So it’s ironic that in the three decades since she showed so clearly that replacing processed food with whole food could rapidly improve blood glucose levels, Australia’s consumption of highly processed foods has grown - along with rates of type 2 diabetes.

Discretionary foods now make up a large slice of the nation’s diet. On average, around 35 per cent of energy in Australians’ diets comes from these foods- and for indigenous Australians it’s 41 per cent. Meanwhile, Australia’s rates of type 1 and type 2 diabetes tripled between 1989 and 2015 and indigenous adults are now 3.5 times more likely to have diabetes than non-indigenous adults.

“So many foods with a longer shelf life are high in fat, sugar and refined carbohydrates and this is very different to traditional foods,” says Professor O’Dea, former Director of the Sansom Institute for Health Research at the University of South Australia where she’s now Professor Emeritus in the School of Health Sciences.

“I’m not an advocate for high protein diets but I do believe adequate protein is important. Many highly processed foods are low in protein and this may contribute to overeating,” she adds, pointing to the protein leverage hypothesis proposed by the University of Sydney’s Professor Stephen Simpson and Professor David Raubenheimer. It suggests that humans have a fixed target for protein and when our diet delivers too little, we keep eating in order to reach that target,

So what will it take to get Australians to eat less processed food?

“If I had any power, highly processed foods would be heavily taxed to encourage consumers to buy more whole food.

“Nutrition should also be a major component of medical education -we need more doctors who recognise the incredible importance of nutrition for preventing disease,” says Kerin O’Dea who once recommended doctors should be able to write prescriptions for subsidised healthy foods for people in remote indigenous communities.

This is where the current focus on the microbiome’s influence on disease could make a difference.

“I think the new understanding of the microbiome is the most important direction in recent medical research. It’s also sparking a new interest in diet among people, including doctors who, until now, haven’t been interested in nutrition,” she adds. “It’s raising awareness of the need to eat healthy foods that are more slowly digested. “

As for making it easier for indigenous communities to access affordable fresh food in rural and remote areas, there’s a long way to go but there are programs such as Outback Stores to make fresh food more available and to reduce the promotion of soft drink, she says.

“There’s also a lot of interest among indigenous people to get into the bush to hunt and fish - but without transport it’s difficult for them to do that.”

Her time in the Kimberley back in 1982 did more than demonstrate the power of food and movement to normalise blood glucose levels. They also taught her that indigenous Australians weren’t so much hunter gatherers as people with well-developed systems for maintaining a food supply.

“They burnt off areas of dry grass so that green shoots would soon appear and attract kangaroos, for instance. They would dig for wild yams but leave a small piece of root so the plant would continue to grow. I got a huge education in those seven weeks. The idea of terra nullius is an outrage,” says Kerin O’Dea who believes Dark Emu, the book by Bruce Pascoe that sheds fresh light on how indigenous people managed and cultivated their land before white settlement is required reading.

Her interest in traditional diets also includes the Mediterranean Diet -she’s involved with the AusMed study, a randomised controlled trial led by Professor Catherine Itsiopoulos from Murdoch University, looking at the efficacy of a Mediterranean diet for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

“There’s no single best diet but the Mediterranean diet is a healthy style of eating - and I think that, compared to Anglo-Australians, many migrant groups such as the Italians and Greeks have managed to hold on to a more traditional way of eating - probably because they’re from countries with a stronger food culture.”

In 2004 Professor Kerin O’Dea was awarded Officer, Order of Australia (AO) for "service in the areas of medical and nutrition research, to the development of public health policy, and to the community, particularly Indigenous Australians through research into chronic disease and prevention methods".

Professor Kerin O’Dea presented a webinar for Education in Nutrition describing her landmark study. You can register for free access to a recording of here webinar here, and read a review of her webinar here