Managing conflict of interest in the age of social media. Paula Goodyer

Paula Goodyer

Paula Goodyer

When it comes to slinging mud on social media, conflict of interest can be a convenient weapon.

”It’s not hard to accuse someone of conflict of interest on social media and most people will not check the accuracy or the context of the information, “says Jacques Rousseau, lecturer in ethics and critical thinking at the University of Cape Town. “The way we’re judged can be different in the age of social media - there are more people who can join in to criticise or praise us and therefore influence other people’s perceptions of us. We are accountable to a far larger group of people.”

This can be especially tricky for anyone working in nutrition - accusations of conflict of interest are sometimes used by groups pushing a particular way of eating to target anyone with an opposing point of view, he adds.

And defending yourself against these accusations on social media might not be easy either.

“You can be faced with strangers looking for a fight and looking for the worst possible interpretations of what you are saying or doing,“ says Rousseau whose presentation Conflicts of Interest in the Age of Social Media delivers a detailed understanding of the complexities of conflict of interest and how best to manage them now.

Dietitians need to manage conflict of interest very carefully, and not rely solely on codes of conduct laid down by professional organisations, he says - they may not have evolved to apply to the current climate.

So what counts as conflict of interest?

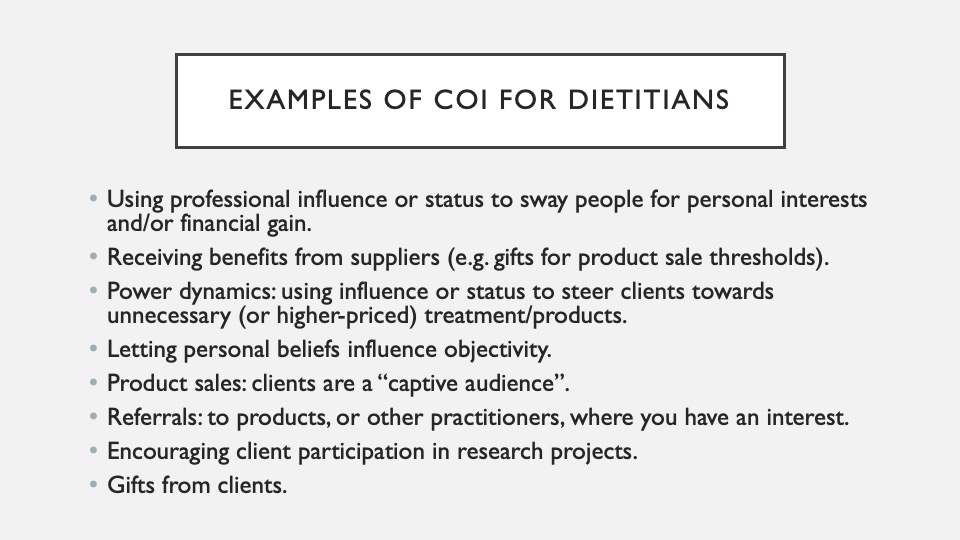

Some COIs are obvious - expensive gifts from a supplier in return for meeting a sales target, or conference air fares covered by a food company. Others are more subtle like letting personal beliefs about food influence your objectivity when advising clients about diet, Rousseau says. If you have a client who wants to follow a diet you object to - Paleo, for example - you might have to help them find the optimal version of that diet despite your objections.

The client-dietitian relationship itself has the potential for exploitation because it’s one of unequal power - e.g. the client defers to the dietitian’s advice and the dietitian refers the client to products that she/he sells or to another practitioner who might be a business partner.

How can you protect yourself against accusations of COI?

Build in as many safeguards as you can is Rousseau’s advice.

”Be slightly paranoid - ask ‘is there anything here that anyone could perceive as problematic?’” he says, adding that besides avoiding CoI, you also need to avoid perceptions of CoI which can be equally damning. Disclosing everything, however small, that could possibly provoke questions about your independence helps you defend yourself later on if problems arise.

Some key principles

Informed consent. Is there any relevant, or potentially relevant, detail the client should be aware of, e.g. “I should let you know that this doctor/health professional I’m referring you to is a friend of mine but she’s also the best person in the business in my experience.”

Providing options. If you’re recommending a particular product that you sell, make it clear that there are other options -e.g. other places to source the product or other products to try that will not compromise treatment.

Reassurance of lack of bias

- It’s not appropriate to endorse products in the media.

- Have strict rules about attending sponsored conferences, e.g. which sessions you participate in, use a disclaimer on slides and don’t allow any pre-presentation vetting of what you say.

The DORM Principles (from The Jurisprudence Handbook for Dietitians in Ontario, 2014)

- Disclosure of the potential conflict: While it’s not always salient, failure to disclose anything potentially relevant is always a breach of professional duties.

- Options: Giving clients alternatives to treatment, encouraging second opinions.

- Reassurance: That they will not be prejudiced by seeking other advice, or buying other products. You will still fulfill your fiduciary duties regardless.

- Modification: Some perceived or actual conflicts can easily be managed. For example, selling products at cost-price mitigates against suspicions.

Squaring up to the ‘assassins veto’

While it’s smart to be cautious because of social media, we shouldn’t be bullied into silence either. This is what’s known as the assassin’s veto or heckler’s veto- when someone is so intimidated by the barrage of criticism of something they’ve said or a stand they’ve taken that they stop speaking up, Rousseau explains.

But this can set us up for long term problems - if we all shy away from speaking up, we risk setting the bar too low for what counts as controversial and soon there is no space to say anything, he says.

“We need to be able to defend a subtle and complicated point of view and in science this is crucial. The world is looking for easy answers - which are usually false - and we need to keep a way of encouraging people to recognise the nuance and complexity of scientific debate.”

Jacques Rousseau is the co-author of Critical Thinking, Science and Pseudoscience (Springer Publishing Company).